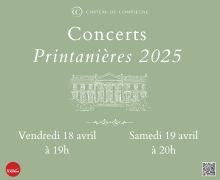

Plus de détails

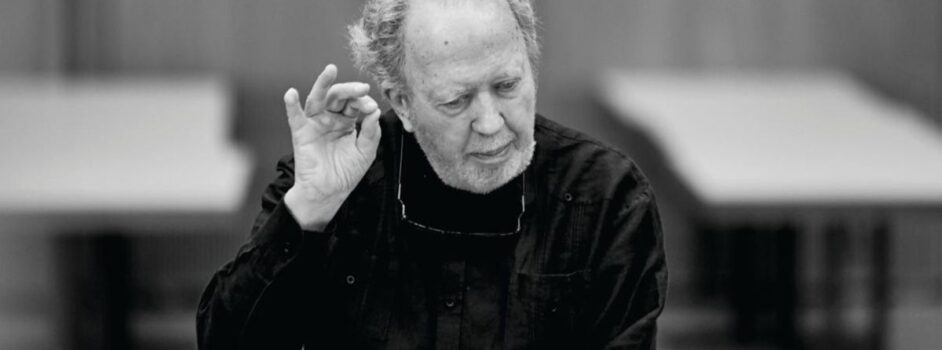

The pianist Leif Ove Andsnes is one of the most creative musicians of his generation; each of his recordings is a significant event. We met him in Stockholm to discuss his latest album, to explore ways in which he approaches the repertoire, and learn details of his chamber music festival.

The pianist Leif Ove Andsnes is one of the most creative musicians of his generation; each of his recordings is a significant event. We met him in Stockholm to discuss his latest album, to explore ways in which he approaches the repertoire, and learn details of his chamber music festival.

« With great music, its value shows itself after a while. My approach does not come naturally. »

ResMusica: Regarding your recent CD, what inspired you to come back to Chopin?

Leif Ove Andsnes: Well, actually, the project of Chopin's Ballades was something I had been thinking of doing for years, and I didn't know if I was ready for it. There was one piece, the Ballade in F minor, which I hadn't studied until six or seven years ago. It's the most complicated, I think, musically, and also pianistically, so it kept me away, not only from the whole project but also from the recording process. For me, it was always the core of Chopin and, by the way, the heart of the Romantic piano repertoire. I don't know why it took me so long to play Chopin again after my first recording. I had played his work but not recorded him, and I think he is a very vulnerable composer. On the modern piano, his music can quickly become bombastic, which is not only sometimes.

RM: What is your secret in preparing an interpretation?

LOA: I think basically it is to work with the score, with the material. I am trying to discover for myself all the storytelling that may be there, and by working on the material, the tale becomes more and more complex and richer. Usually, with great music, its value shows itself after a while. My approach does not come naturally, so I need to find different ways, which must be more extreme here and there. A lot of people play the piano well, but, you know, everything happens from some kind of intuition, which is terribly important. I mean that very often this feeling establishes the first idea, but then you have to really think what happens. In regard to additional musical factors, I would say that they are really secondary, but are, of course, interesting to know. For example, I'm interested in knowing about the composer, but I don't use that information consciously in interpreting the work. The ballade is perhaps the most descriptive title we have from him. And yet, he doesn't give us any program. His Ballade in F major is a kind of portrait of Schumann, I think, because it was dedicated to him and has “separate” episodes. In some parts, it is very innocent and pure, which brings to mind a reflection of Schumann, his alter ego. Then, there is the wild side, which continues through to the very end, and the coda, of course, which is explosive. Though at the end again, you see the structure in an intimate, sad way, so I am reasonably sure that the work is a kind of portrait of Schumann.

RM: I like your remark about intuition. That first, there is something that comes intuitively and then you work on it. It was the same with Chopin.

LOA: I mean he's such a sophisticated composer, and there was a lot of thinking and calculation involved in what he did, but as you say, I'm sure the first idea very often came from the fingers while he was sitting at the piano. I think so much of the music from this composer came from that process, a kind of improvisation, you know, maybe not always with the piano, but also from imagining at the piano. And this music is so born from the fingers; it fits them like a glove, and could not have been written for the orchestra.

« Pianists ignore the left hand all the time because our ear goes so quickly to the right hand. »

RM: Would you have a piece of advice for young pianists regarding practising?

LOA: When I teach, there are some things that I always come back to. You know, I think pianists ignore the left hand all the time because our ear goes so quickly to the right hand. What I talk about most when I teach is the consciousness of the left hand, the basis of everything, from a technical point of view. I emphasize the idea that one should feel the left hand as the conductor. It has to feel the figure first, and then the right hand follows along much more readily by itself.

RM: What is the importance of chamber music in your artistic life?

RM: What is the importance of chamber music in your artistic life?

LOA: Chamber music has been essential in my life. It still is, but especially when I began playing concerts, I played a lot of this music with different Norwegian artists and other players. Later on, I met the violinist, Christian Tetzlaff, and we played many duets together. I cannot imagine life without chamber music because there is nothing more natural than just to get together with a few friends to play that music, just as people did in the old days, and that how you socialized at home as well. If you were an amateur musician, you played together with friends, and it's a terrible loss in today's society that we don't have this natural way of making music at all different levels. But that's how so much of this music is born, and it still occupies a very natural part of my activity, though I am doing less of it. In my family, we had our first child nine years ago, and now we have three, and as my family grew, I reduced the number of my concerts. Unfortunately, I also cut quite a bit of my chamber music activity, so now I do one or two projects with some artists, and I have my own festival in August every year, in Rosendal, Norway. I know some pianists who say they would never accompany lieder singers although I cannot imagine how that can be. I mean not to play Schubert's cycles, or work with a great singer, or on a Brahms quartet?

« Chamber music has been essential in my life. »

RM: Regarding your festival, what kind of event is it?

LOA: It runs for four days, and it's very concentrated: ten concerts, some lectures, and about 20 musicians. This year, we also have a string orchestra, so there will be more musicians, and the idea is that most of the musicians stay for the whole period, and we don't have an artist doing only one recital, but rather, they participate in different programs. I like to really keep to one theme, so last year, for instance, we played only music from the First World War, pieces written between 1914 and 1918, and it was very interesting. We had fantastic experiences listening not only to Zemlinsky's String Quartet n° 2, which is a kind of bridge between Mahler and Schoenberg, but also to works by Charles Ives, Scriabin, Bartók, Nielsen and Elgar. It was from late Romantic to Anton Webern, which let us have a whole spectrum of expressionism.

RM: Were there any discoveries of a not well-known repertoire?

LOA: I mentioned Zemlinsky's String Quartet n° 2, an absolutely amazing piece. Also, I played a piece by Busoni for the first time: an improvisation for two pianos over Bach's chorale. It was my first piece by Busoni. I also did the Piano Quintet n° 2 by von Dohnányi, which was a great discovery for me. Also, Charles Ives' Concord Sonata, played by Bertrand Chamayou, was such an event.

Pictures: © Chris Aadland, Gregor Hohenberg