Plus de détails

« There is no replacement for reaching out and taking time to create lifelong connections to the arts. »

« There is no replacement for reaching out and taking time to create lifelong connections to the arts. »

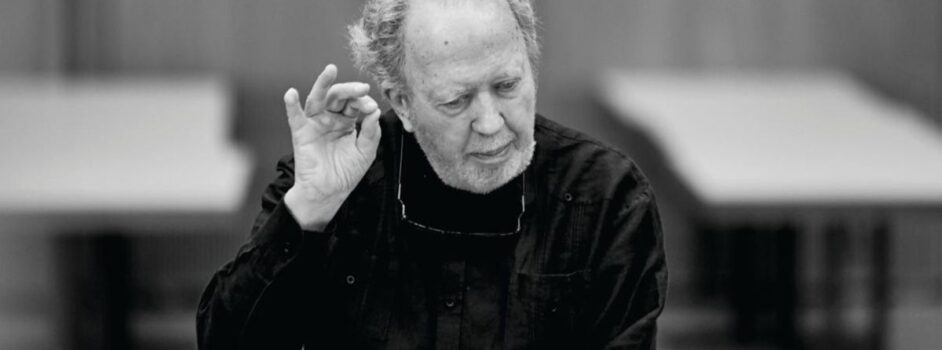

Winner of the Sir Georg Solti Conducting Award in 2013, James Feddeck has held the posts of Assistant Conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra and Music Director of the Cleveland Orchestra Youth Orchestra. In this interview, Feddeck discusses his broad musical background, guest conducting on short notice, and this thoughts for reinvigorating classical music audiences.

ResMusica: You began your conservatory training as not only a conductor but also as an organist, pianist, and oboist. How and when did you decide to focus your career on the organ and conducting?

James Feddeck: Music was always very much a significant part of my life's focus, but it was a difficult challenge to determine which aspect of music would be a priority. In my earlier years as a musician it never occurred to me that I would need to “specialize”, and as I looked to the great musical figures of the past as an example, it seems neither did they. Nonetheless, conducting was a very natural way to bring all of my musical interests together, as well as the joy of making music with many people to combine multiple forces into a singular vision. It also remains personally paramount to continue to perform myself, to remain very much in-touch and sympathetic to the practical demands and considerations of the orchestral players with whom I work. For that reason I continue to play the organ, piano, and oboe and try to perform on these instruments as much as possible.

RM: Do you feel that your background as an organist has influenced your approach to conducting an orchestra? If yes, how so?

JF: My initial attraction to the organ as a young child was because of the wondrous and seemingly endless possibilities for color and sound. I remember spending hours experimenting and combining different stops on the church organ when I was just 8 years old. My study of the organ resulted in the development of an immense sonic imagination which I now use to further investigate the limitless possibilities for sound with an orchestra. There is also no such instrument or repertoire that develops as much an individual's ability to hear, play and study counterpoint as the organ. These have been invaluable contributions to my work as a conductor.

RM: Who would you say are your conducting “heroes,” and what role have they had in your development as a conductor?

JF: I have had the great fortune to be exposed to many great teachers and mentors in the crucially formative years of my study. Perhaps the most significant has been David Zinman, with whom I spent several years, first as a student and then as his assistant at the Aspen Music Festival. Mr. Zinman's approach, particularly in the works of Schumann and Beethoven completely opened these worlds to me in an entirely new way, as did his general approach in varied repertoire of all kinds. His passion for teaching, his commitment to the future generation, and his generosity toward those with whom he works have been a great inspiration and humbling reminder to me of what a true leader should be.

RM: You started gaining international recognition as a conductor after stepping in on several occasions for top conductors on short notice. What have been the challenges and rewards of conducting under these kinds of circumstances?

JF: It is always a challenge to meet an orchestra for the first time and admittedly, as a guest conductor it can be a somewhat artificial relationship due to inherent time constraints. After only a few short days together we must create a deeply committed and emotionally persuasive performance. In the cases of stepping in on short notice there is the added excitement of the unexpected surprise that the cancellation creates. I have found these circumstances to be even more of a thrill, and typically after the first few minutes of our work together, the orchestra is at ease, just as if it were a planned appearance. But the anticipation is probably the hardest part of those circumstances.

RM: Many orchestras are deeply concerned about audiences that are both decreasing in size and increasing in age. As a young conductor who has also worked extensively with young musicians, do you have any thoughts on this concern, and how it could be addressed?

JF: There is an extraordinary paradox in the current world of orchestras. On the one hand statistics exist to show decreasing audiences, subscriptions, etc. but on the other hand there are a record number of music students, particularly on the conservatory and university level who seemingly are able to perform at an increasingly higher level, for whom music is a crucial, indispensible way of life. Certainly gone are the days that age mattered in this business, if it indeed ever mattered. I've worked with young pianists, violinists, youth orchestral players who were in every way just as “good” as mature adults. What matters most and what makes a brilliant performance, beside the obviously required technical proficiency, is that artists have something to say in their music: this is the defining factor of the quality of an artist. I have found, therefore, that age is completely irrelevant to music-making except as a mere factual observation just as hair color or height.

Is it really a surprise that as the musical presence in schools have diminished, as curricula have turned focus away from classical music, that the audience base for classical music has also diminished? There have been various models to experiment with the cost of tickets and making them more affordable to young people, but is this enough? Does this create a relationship, understanding, and appreciation for the art form? There is no replacement for reaching out and taking time to create lifelong connections to the arts. Music education at a young age is crucial to holistic development and its benefits reach beyond practice and performance and into crucial processes such as problem solving, logic and mathematics, language, social skills, as well as other disciplines. Classical music has even made its way out of the concert hall and into laboratories where compositions of Mozart and Bach are analyzed for its clinical and psychological benefits.

The key to the solution, in my opinion, is to encourage people to make music. If a young person plays a musical instrument, even if he will ultimately become a doctor or engineer, he will have an understanding and a love for the art and is more likely to be a season subscriber, board member, donor and advocate and will do the same for his children. The same could be said for an adult who participates in a chorus or community orchestra on Tuesday evenings after work. In our age of technology and on-demand entertainment, we have seriously gone away from making music and maintaining its value on a personal level compared to previous times. It is not just attendance; orchestras need to do everything possible to encourage music-making for all ages and all levels of ability. It is only in this way that I believe we will see resurgence in the number of people who have a direct and personal relationship to music.

RM: Do you have any particular plans for the future? Are there any projects or areas of repertoire you wish to explore? Any thoughts of having an orchestra of your own?

JF: For the foreseeable future I will continue my work as a guest conductor, pursuing as many different aspects of the repertoire as I can. I enjoy all parts of the orchestral canon, from contemporary music, to the big romantic works, the witty classical repertoire and baroque music which is the foundation of it all. I think it is very important to be able to offer informed performances of all these styles and is altogether too easy to be dismissed as a champion of only one part of the repertoire. I am also drawn to the great choral-orchestral works which likely comes from my organ background and previously extensive work in church music since an early age.

I would love to have an orchestra of my own, however, frankly speaking, I do not feel rushed to do so. When one talks about the relationship of the music director to an orchestra, one must keep in mind that it is a very special one. This is someone with whom the orchestra will spend considerable time and who really shapes the nature of the orchestra in a long-term way both musically and institutionally. It must be a great fit, and it must be a place willing to commit equally to the artistic excellence and innovation our musical landscape deserves.

Credit Photo : James Feddeck (c) Benjamin Ealovega

« There is no replacement for reaching out and taking time to create lifelong connections to the arts. »

« There is no replacement for reaching out and taking time to create lifelong connections to the arts. »