Plus de détails

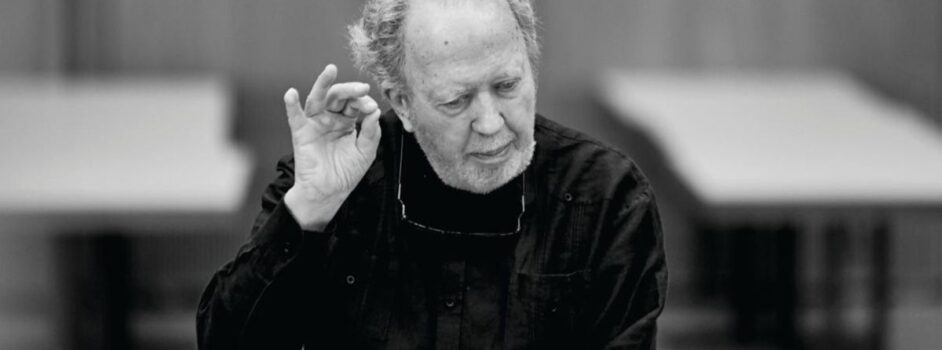

Joseph Silverstein has been the concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1962 for 22 years. During his tenure, he expanded his life in music to chamber music, before becoming music director for 20 years of the Utah Symphony Orchestra and the Florida Philharmonic Orchestra. Today a professor at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, he was in Paris as a jury member of the 71th Long-Thibaud-Crespin competition. Interview with a violin master with a long history but who prefers our time.

« Hilary Hahn or Frank Peter Zimmermann reached a level of virtuosity which is well beyond what preceded them »

« Hilary Hahn or Frank Peter Zimmermann reached a level of virtuosity which is well beyond what preceded them »

ResMusica: You have been the concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1962 for 22 years, playing with conductors such as Charles Munch, Pierre Monteux, Erich Leinsdorf, Seiji Ozawa… For many music lover, this was a legendary time for the orchestra.

Joseph Silverstein: The Boston Symphony Orchestra is phenomenal since I left! Musicians retired have been replaced by new players with extraordinary virtuosity.

RM: Music is also a question of style, not only virtuosity… Do you miss the style of the old BSO?

JS: At that time, style was very much influenced by the music director, who was present 3/4 of the season. Today, music directors cut the time they spend with the orchestra, and the style is created by the musicians themselves who brings sophistication at a level not heard before. For instance, a solo wind player today has a well-defined concept of the Marcia Funebre of the Eroica, and he brings this knowledge to the orchestra.

RM: Paris will open its new philharmonic hall in January. Do you think it will help improve the artistic level of the orchestras?

JS: Of course it will! When the Utah Symphony, which I directed from 1983 to 1998, started to play in their new concert hall, which is among the finest in the USA, it was like there was another instrument in the orchestra. The hearing was so natural, it was creating a natural assemble.

RM: You were not only the first violin of the BSO, but you were also playing chamber music. Was a natural expansion of your activity?

JS: You must realize there was a lot of professional type casting at that time. I became concertmaster with Erich Leinsdorf, which exposed me to become a soloist. I decided it was a good idea to form a chamber music group. Leinsdorf agreed it would be good for the orchestra, and good to have musicians playing mixed ensembles for string and winds. It became very much part of our activity as part of the BSO. The repertoire was decided by our committee, we made many tours and recordings, the Histoire du soldat is still on the catalogue after many years. The BSO was the first to have its own chamber music, the first with set personnel, it's more conventional now. It was a happy extension.

RM: So the silos between orchestra musicians and chamber musicians tend to disappear?

JS: Many of the young musicians who are forming quartets and trios have started in places like Marlboro, it's hard to see if this move comes from the orchestra or goes to the orchestra. In any case, the audience likes more the intimate nature of chamber music. We live in an era of hyperbolic noise, the sound volume in cinemas are so high, to hear string quartet is almost of relief of our noisy life.

RM: You mentioned the professional typecasting you were facing in the 60's. I suppose becoming a conductor was not a natural evolution for a concertmaster?

JS: It was not. We chose Michael Tilson Thomas as associate conductor. I was conducting as a duty for educational purposes. On one occasion he was not available and I was its only choice. It seems I did reasonably well, but I never stopped playing the violin. My identity as a musician was too deeply about playing the violin.

RM: You started your career more than 6 decades ago, how do you see the musical world changing?

JS: It is more competitive today and there are much greater opportunities. When I was young, you had to be in the “big five” or you were not really in a career. Today my students at Curtis are in a string quartet, a concertmaster at Radio Köln, associate concert master at the Kansas Symphony, they have a life in music, rather than a « career » which is limited. I encourage them to pursue the various opportunities.

RM: You mentioned earlier the greater virtuosity of todays' musicians…

JS: Yes, the physical command of the instrument has become much higher in 20 years. The big difference has been created by electronic reproduction. Hilary Hahn or Frank Peter Zimmermann reached a level of virtuosity which is well beyond what preceded them. Musicians at a very early age believe this is the way it should sound and they are not limited by teachers who tell them it's too difficult. Also they hear so-called original instrument play, they are exposed to style which cover 400 years. Alan Gilbert plays all Nielsen symphonies in New-York, James Levine celebrated Elliott Carter's 100th birthday by playing a lot of his works with the BSO. 20 years ago no one would have played Janáček, Hindemith or the Elgar violin sonata. All this makes musicians far more sophisticated about musical style.

RM: You have also being teaching in China. How do you explain the importance of classical music there?

JS: This music is about us. The intense response to western art music is the best example of its universality. If you look at a brain scan, you see that major and minor sounds bring a difference in the response. : Mozart plays with our experience, and when a Chinese audience listen to one of his symphonies, it is responding in the same way as in Paris.

RM: In everything you seem to see the positive side. You are a very optimistic person!

JS: I am 82 and I have been a professional since 1947. At that time, Mahler and Bruckner were very rare, Haydn was limited to the London symphonies. Today orchestras play Schubert symphonies 2, 3 and 4, the Czech suite by Dvořák, all these works we did not know, and in the process the orchestras play better. I see all these young musicians who are studying the violin, which is not easy! Why do they do that? Probably because of the personal expression it makes possible, because of the depth of experience brought by composers. If this kind of desire persists, there must be something good about it.

Photo : (c) Joseph Silverstein

Plus de détails

Joseph Silverstein has been the concertmaster of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1962 for 22 years. During his tenure, he expanded his life in music to chamber music, before becoming music director for 20 years of the Utah Symphony Orchestra and the Florida Philharmonic Orchestra. Today a professor at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, he was in Paris as a jury member of the 71th Long-Thibaud-Crespin competition. Interview with a violin master with a long history but who prefers our time.

« Hilary Hahn or Frank Peter Zimmermann reached a level of virtuosity which is well beyond what preceded them »

« Hilary Hahn or Frank Peter Zimmermann reached a level of virtuosity which is well beyond what preceded them »