Plus de détails

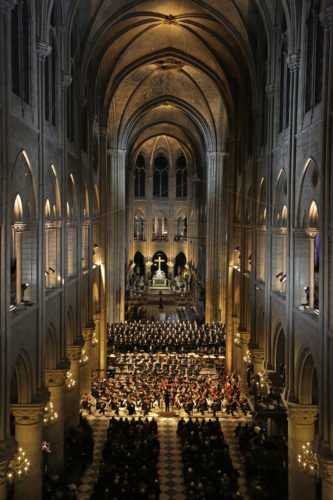

Paris. Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris. 22-I-2014. Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) : Grande messe des morts. Andrew Staples, ténor. Choeur de Radio France (chef de chœur : Celso Antunes) ; Maîtrise Notre-Dame de Paris (chef de chœur : Lionel Sow) ; Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Orchestre Symphonique Simón Bolivar du Venezuela, direction : Gustavo Dudamel

A performance of Berlioz's Requiem is always a special occasion, because of the number of people involved (almost four hundred), the space required for effective spatialization of the four different brass orchestras, and the expressiveness of the score, which was written a few years after the Symphonie Fantastique by a thirty-four-year-old visionary genius.

In the choir at Notre-Dame de Paris, genius conductor Gustavo Dudamel mastered the venue's acoustics while leading a superbly prepared ensemble of instrumentalists and singers. He served to the utmost the score of this great mass for the dead, spectacular in its sudden sonic upsurges as well as the abyssal silences that Berlioz sets in the heart of his sonic dramaturgy.

In the choir at Notre-Dame de Paris, genius conductor Gustavo Dudamel mastered the venue's acoustics while leading a superbly prepared ensemble of instrumentalists and singers. He served to the utmost the score of this great mass for the dead, spectacular in its sudden sonic upsurges as well as the abyssal silences that Berlioz sets in the heart of his sonic dramaturgy.

A few minutes were needed to get used to the location, but then Dudamel, conducting without baton but with the score, took us with him into Berlioz's particular universe. As soon as the simple and quite short Kyrie starts, the excellent work of the choirs (the Radio France choir and the Maîtrise de Notre-Dame de Paris) was evident, especially in the enunciation of the text, which was pronounced à la française (with a French accent, as Latin was pronounced in France in Berlioz's time). In the beginning of the Dies Irae, considering how demanding Berlioz's writing is at this point, the flexibility of the voices in each section was pure bliss. In the “Tuba mirum,” the interjections of the four brass ensembles, located in the higher sections of the nave, ignite the resonant space. The even more extreme treatment of the sound masses in the “Rex tremendae,” which is the first climax of the work, is admirable under Dudamel's conducting, with gestures as thrifty as they were masterful. The “Quarens me,” a strong contrast to the preceding section, is sung a capella, in a gentle tempo and always sostenuto, in an exemplary fashion by the two choirs, in a very expressive, continuous flow of music. Dudamel kicks off the Lacrymosa at a brisk clip, putting all the assembled forces to the test. He unleashed the orchestral machine—the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France and Venezuela's Bolivar Orchestra—without ever leading it astray, the balance between voices and orchestra remaining immaculate in the Dies Irae's last verse.

The orchestra tuned up once more before the Offertoire, an especially Berliozian movement, in which the composer superimposes two temporal layers: the psalmody, and the orchestra's fugal material. Berlioz used this newly discovered texture again in his choral symphony Roméo et Juliette a few years later. However, it did not appeal to Dudamel, who gave this section extra weight without emphasizing the horizontal dimension of the writing. The Hostias is the “experimental” section of Berlioz's work, the one in which he explores pedal points for the trombone and flute, in order to reinforce the impression of vast, even infinite spaces. Experiencing the work as a listener is always gripping.

Berlioz wrote only one solo aria in his Requiem, in the Sanctus. It is initiated by a fragile tremolo in the violas, a moment of rare emotion. The tenor writing is especially difficult, demanding, as always with Berlioz, a flawless flexibility and a voice of impressive scale in order to nourish the elegant melodic line, full of expressive curves. The luminous voice of English tenor Andrew Staples (a substitute for Andrej Dunaev) possesses all those qualities. He was very impressive in this part, where Berlioz shows all his talent as a melodist. The slightly academic fugue in the Hosanna serves as a short respite for the tenor, before his aria is performed again, with women's voices as an echo. The composer then adds some cymbal rustles to color the silence: a stroke of genius.

At the end of the Agnus dei, the last part of the work, Dudamel, the evening's phenomenal master of music, maintained about thirty seconds of eloquent silence before letting the audience make itself heard.

Crédit photographique : © Jean-François Leclercq/France Musique

Plus de détails

Paris. Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris. 22-I-2014. Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) : Grande messe des morts. Andrew Staples, ténor. Choeur de Radio France (chef de chœur : Celso Antunes) ; Maîtrise Notre-Dame de Paris (chef de chœur : Lionel Sow) ; Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Orchestre Symphonique Simón Bolivar du Venezuela, direction : Gustavo Dudamel