Plus de détails

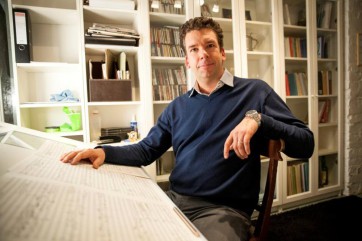

Sebastian Fagerlund (b. 1972) is one of the leading Finnish composers of his generation. Championed by conductors such as Sakari Oramo and Dima Slobodeniouk, in 2011 Fagerlund was awarded the most prestigious music award in Finland, the Teosto Prize, for his orchestral work Ignite. The same year Ignite was also selected as a recommended work at the International Rostrum of Composers in Vienna. Here Fagerlund talks about his origins as a composer, the process of composition, his breakthrough, as well as future projects.

ResMusica: What was your first encounter with classical music?

ResMusica: What was your first encounter with classical music?

Sebastian Fagerlund: I was born in a small archipelago town in the southwest of Finland called Pargas. There was not much classical music or high culture present in the city, but in my family classical music was often listened to and discussed. My parents took me from a very early age to symphony concerts, for example in the nearest larger town called Turku. Home concerts were arranged by my family and their friends from time to time and I also got acquainted with my parents' quite extensive record collection of classical music at an early age. I have a very vivid childhood memory from a situation where I must have been about 4 years old. I watched a black and white television broadcast of a concert where David Oistrakh played as a soloist with an orchestra. It left an enormous impression on me and I started to dream about playing the violin. At the age of 5, after several attempts of trying to imitate playing the violin by using a guitar and my grandfather's horsewhip as a bow, my parents and grandparents decided that I should have the opportunity to start studying violin. I did not grow up solely surrounded by classical music though. Throughout my life I have also been very interested in what is happening and developing in different musical genres and what I could learn and what experience I could gain from them.

RM: What was the experience(s) that convinced you to be a composer?

SF: There is no specific experience that I can pinpoint. I was already as a child interested in trying to write music. While growing up, I gradually came to understand that composing had a stronger importance to me than playing or performing. My violin studies stayed with me through my late teenage years and up to my early twenties. While still living in Turku, I played gigs as a substitute player in the Turku Philharmonic Orchestra. This was enormously educating because I got to perform a large amount of the standard symphonic repertoire sitting right in the middle of the orchestra in the 2nd violin section. Actually experiencing the physicality of the sound at a highpoint of a symphony was a great addition to the understanding of a piece, along with reading the same score at home and listening to it within your own head. Eventually, during this time composing took over so much that I found less and less time to practice and I turned to study composition.

RM: Who would you consider to be your compositional heroes?

SF: I think every composer has different heroes at different stages of one's development. But if I would try to single one out I would have to say Witold Lutoslawski, though our musical expression may seem very different. I remember that his orchestra piece Livre pour Orchestre already made a huge impact on me when I was really young and I have returned to this piece several times during both my studies as well as during my career. As a young boy I might not have had the ability to analyze the piece to the same extent as a composition student, but his musical expression made me realize that there was something extraordinary happening in his music. During my study years I felt Lutoslawski's music, especially Livre pour Orchestre, gave me insight into the concept of dramaturgy in music and different ways of looking at material development.

Of living composers I recall a brief meeting with Mark-Anthony Turnage at a composition summer course in Porvoo in Finland in the mid 1990s. This was a course that took place at the same time as the Avanti! Summer Sounds Festival. Turnage had made his breakthrough with Blood on the Floor and Esa-Pekka Salonen had invited him to the festival. We were about 10 students and I doubt that Marc-Anthony even remembers this short meeting–he seemed quite overwhelmed with all the attention! However, it later made me reflect on yet another way of composing music and also the importance of being aware of what is going on around you as a composer.

RM: Where did you receive your compositional training? Who were your teachers and how did they influence you?

SF: I have studied composition at the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki. My teacher was Erkki Jokinen. I would say that he really taught me the craft of composing; the challenging detailed work of both the technical side of composition as well as orchestration but most importantly being aware of tradition and your own relationship to it. One thing he taught me which I fully realized much later was that we are always surrounded by and part of different aesthetics, stylistic guidelines and invisible boundaries. The thought of absolute 100% stylistic freedom is an illusion and you can only achieve a real sense of freedom by being aware and knowing as much as possible of the long river of music history that we all are part of and that surrounds us.

RM: What would you say was your first major “break” as a composer?

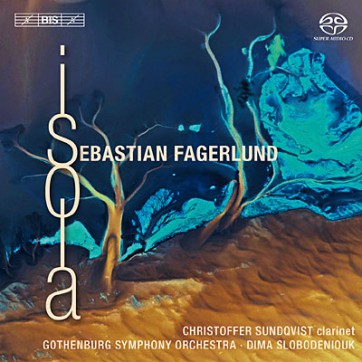

SF: The Clarinet Concerto. The piece was commissioned by the Korsholm Music Festival and my long term musician friend, the clarinetist Christoffer Sundqvist. The premiere was a success but the ramifications over the following years were even larger. Sakari Oramo heard the recording of the premiere and immediately wanted to record and perform the piece with the Finnish RSO. The radio recording with Oramo and the Finnish RSO found its way to Edition Peters, with whom I signed a worldwide publishing deal the following year. Not long after that, Robert von Bahr from the record company BIS contacted me after hearing the recording and we started a collaboration. Shortly afterwards, the Clarinet Concerto was recorded with the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra conducted by Dima Slobodeniouk. This autumn the next CD with my orchestral music will be released. The recording will feature the large orchestral work Ignite and my Violin Concerto performed by Pekka Kuusisto (the dedicatee), with Hannu Lintu conducting the Finnish RSO. The Clarinet Concerto has also started to live its own life in the concert programs of different orchestras; last spring it received its UK premiere with the BBC SO, and recent performances were just a few weeks ago, 18-26 January 2014 when the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie in Germany completed a tour in Germany with the Clarinet Concerto on the program featuring Christoffer Sundqvist as soloist.

SF: The Clarinet Concerto. The piece was commissioned by the Korsholm Music Festival and my long term musician friend, the clarinetist Christoffer Sundqvist. The premiere was a success but the ramifications over the following years were even larger. Sakari Oramo heard the recording of the premiere and immediately wanted to record and perform the piece with the Finnish RSO. The radio recording with Oramo and the Finnish RSO found its way to Edition Peters, with whom I signed a worldwide publishing deal the following year. Not long after that, Robert von Bahr from the record company BIS contacted me after hearing the recording and we started a collaboration. Shortly afterwards, the Clarinet Concerto was recorded with the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra conducted by Dima Slobodeniouk. This autumn the next CD with my orchestral music will be released. The recording will feature the large orchestral work Ignite and my Violin Concerto performed by Pekka Kuusisto (the dedicatee), with Hannu Lintu conducting the Finnish RSO. The Clarinet Concerto has also started to live its own life in the concert programs of different orchestras; last spring it received its UK premiere with the BBC SO, and recent performances were just a few weeks ago, 18-26 January 2014 when the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie in Germany completed a tour in Germany with the Clarinet Concerto on the program featuring Christoffer Sundqvist as soloist.

RM: Tell us a little bit about your compositional process. What are some of your inspirations? Do you find composition to be more of an intuitive process, or a logical process? Do you sit down a write a piece from beginning to end? Or is it more like putting a puzzle together, piece by piece?

SF: I feel inspiration comes to me from continuously working; in other words one piece « feeds » the next and usually when a process is over with one composition I am left with a lot of new ideas and material that grew organically from the previous one. I do not write programmatic music but sometimes an event or place is something I can draw inspiration from. The orchestral work Isola is an example. This piece relates to an island in the Turku archipelago where the mentally ill and women suspected of witchcraft were deported to during medieval times. According to a legend they were only allowed to carry with them the building material for their own caskets. Nowadays, this place is a beautiful island with extraordinary archipelago nature. This combination of great beauty and scenery and the knowledge of the cruelty and suffering just under the surface formed an abstract inspiration for the piece even though it is not a description of the island in itself. Large and majestic sounds rule the orchestra but at the same time dark and unsettling material is pushing through from underneath and gradually taking over.

In the beginning of a compositional process I establish a clear picture of a certain backbone of a piece. The intuitive part comes in when the musical material through the process then starts to grow around this « spine. » I see the process in a way as a combination of craft and intuition. It is both achieving control of the material while at the same time allowing it to grow and observing how far the material can be bent and modified. It is quite a paradox actually; I feel that as a composer you must always focus on sharpening your technical skills and abilities-always pushing yourself further. At the same time, when reaching a certain technical level and a level of control you have to be able with every piece to take a leap. To throw yourself from the cliff you have constructed and rely on intuition.

RM: Listening to your music, one gets the impression of vitality, rhythmic energy, freedom of style, but ultimately a clear narrative sense and flow. Your music is accessible and not music as one might say “written by a composer for composers.” Would you say that you found your compositional voice naturally, or was it a prolonged struggle to reach this point?

Well, it is of course a matter of defining the concept of « a compositional voice. » If by compositional voice you mean a certain similarity between the works in the catalogue of a composer, you can firstly look at it from a musical material point of view. During the last ten years I have gradually come to use certain musical materials with certain characteristics that stand in relation to each other and I am constantly working with developing them and refining them. So from this point of view I think every composer faces a certain struggle. On the other hand, I feel that many things have also come naturally. For example, I feel that working with the orchestra is a very natural medium. Orchestration for me gives me kind of this « child playing in a sandbox » feeling! Always discovering.

RM: Sakari Oramo is an enthusiastic champion of your music. Tell us about this artistic partnership and how it began.

SF: Sakari is a fantastic conductor and musician! He has the ability to really dig deep into the music on a both technical but also emotional level, while at the same time around him creating an aura of positivity and enthusiasm. Sakari became familiar with my music via my Clarinet Concerto as I earlier mentioned. He immediately commissioned a new large orchestral work from me called Ignite which I wrote for the Finnish RSO. At that time Sakari had established with his wife, the soprano Anu Komsi, a new opera festival in the northwest of Finland called the West Coast Kokkola Opera. They commissioned a new chamber opera from me. This resulted in the chamber opera Döbeln. The opera and the recording of it got widespread attention and recognition all over the world. A few years later Sakari and the Finnish RSO commissioned a guitar concerto. Due to many other commissions, I got to realize this production several years later and the premiere took place in October 2013 in Helsinki with the Finnish RSO conducted by Sakari and Ismo Eskelinen as soloist. A month later the Guitar Concerto received its UK Premiere with the BBC Symphony Orchestra in London. It is wonderful to be able to work with such a brilliant conductor over a long time period. I feel I have learned very much and at the same time I think Sakari has gained a deep insight into my expression and musical world.

RM: Finland, despite its small population, continues to create composers of international reputation, such as yourself. What do you think it is about Finland that has allowed it to be so successful in this regard?

SF: When it comes to this subject usually the discussion turns to the Finnish education system. This is of course a factor of major importance but I would also like to bring up that Finland is a small country where the point of focus of the musical life many times is Helsinki. Here there is the Sibelius Academy, the main large orchestras, the National Opera, Ballet, etc. It is a tight network, where from the start composers can have access to musicians and conductors and vice-versa. From a slightly relaxed point of view I could mention St. Urho's Pub close to the main concert halls where everybody goes and meets! Young and old, world-famous, and beginners all meet under the same roof and at best people get advice and access to each other's experience.

I feel very privileged that I have had the opportunity to meet so many musicians and conductors that I have composed for and grown with and become friends with since the study years. This is music making and art in its best form when you can work and grow with people who also develop and become really familiar with each other's expression and language. When people's careers then take them outside of Finland, the same music making continues but the networks grow.

I must add though, that the successes in classical music that many times is mentioned when talking about Finland right now is at risk due to funding cuts in culture, education and short term quarterly-economy thinking; culture is always the first to go when money is tight and populism is growing. What few decision-makers seem to understand is that there are no short term solutions in serious and high-profile art. The results we have seen during the last ten years are a product of decisions made already over 20 years ago.

RM: Tell us a little bit about your upcoming projects.

SF: The end of last year and the beginning of this year I have traveled frequently with different recent orchestral pieces. My orchestral music was performed by the BBC SO, Singapore SO and Italian National Symphony Orchestra RAI. Now I am focusing on composing a Concerto for Bassoon and Symphony orchestra commissioned by the Borletti Buitoni Trust, Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra and Lahti Symphony Orchestra. The piece will receive its premiere by the Lahti SO conducted by Okko Kamu and soloist Bram van Sambeek at the end of this year. I will also work on a new orchestral work commissioned by the Bergen Symphony Orchestra and Tampere Philharmonic Orchestra, which will be premiered next season. In the autumn a new record of my recent orchestral music will be released by BIS. Since last year, together with the clarinetist Christoffer Sundqvist, I have also been appointed artistic director of a new chamber music festival in northwest Finland called RUSK-Chamber Music. The goal of the festival is to present top international artists and one guest composer each year during the darkest and grimmest time of the year.

RM: Where do you see yourself going as a composer? What kinds of challenges would you like to tackle in the future?

SF: I feel I have barely scratched the surface when it comes to orchestral music and this is a path I will continue to explore.

Plus de détails

Sebastian Fagerlund (b. 1972) is one of the leading Finnish composers of his generation. Championed by conductors such as Sakari Oramo and Dima Slobodeniouk, in 2011 Fagerlund was awarded the most prestigious music award in Finland, the Teosto Prize, for his orchestral work Ignite. The same year Ignite was also selected as a recommended work at the International Rostrum of Composers in Vienna. Here Fagerlund talks about his origins as a composer, the process of composition, his breakthrough, as well as future projects.