Poland has been celebrating the 80th birthday of its most famous composer, Krzysztof Penderecki. It is not often that contemporary composers are extolled with such splendor: the National Bank of Poland created a special banknote; the Polish mail service produced a stamp with his portrait; a box set including all his symphonies was published under his direction on the Dux label; there were two exhibitions in the hall of the National Opera and a week-long festival was entirely dedicated to his work. This week culminated in a gala ball at the Warsaw Opera, broadcast on radio and television, with many well-known figures: the President of the Republic of Poland and his Croatian counterpart, who was a noted composer in a former life, as well as countless representatives from the diplomatic and cultural spheres. It all ended in the inevitable presentation of medals and a “Happy Birthday” in Polish and English, the latter directed by Valery Gergiev himself.

Poland has been celebrating the 80th birthday of its most famous composer, Krzysztof Penderecki. It is not often that contemporary composers are extolled with such splendor: the National Bank of Poland created a special banknote; the Polish mail service produced a stamp with his portrait; a box set including all his symphonies was published under his direction on the Dux label; there were two exhibitions in the hall of the National Opera and a week-long festival was entirely dedicated to his work. This week culminated in a gala ball at the Warsaw Opera, broadcast on radio and television, with many well-known figures: the President of the Republic of Poland and his Croatian counterpart, who was a noted composer in a former life, as well as countless representatives from the diplomatic and cultural spheres. It all ended in the inevitable presentation of medals and a “Happy Birthday” in Polish and English, the latter directed by Valery Gergiev himself.

This festival was the reason members of the jury of the International Classical Music Awards (ICMA), of which ResMusica is a member, came to Warsaw: Krzysztof Penderecki had received a special prize in 2012 for his entire career.

The festival offered 51 of his works, covering all genres except opera. The scores were played by the best orchestras of Poland, with some key creators of his works, as well as a myriad of young artists; the young generation has taken up the torch to keep Penderecki's works in the repertoire. Among the great were Anne-Sophie Mutter, Valery Gergiev, Lorin Maazel, Marek Janowski, Leonard Slatkin, and Julian Rachlin. All are linked to the composer's work and are fervent admirers of his art, including the Swiss conductor Charles Dutoit, who called Penderecki “the greatest composer alive.”

The festival offered 51 of his works, covering all genres except opera. The scores were played by the best orchestras of Poland, with some key creators of his works, as well as a myriad of young artists; the young generation has taken up the torch to keep Penderecki's works in the repertoire. Among the great were Anne-Sophie Mutter, Valery Gergiev, Lorin Maazel, Marek Janowski, Leonard Slatkin, and Julian Rachlin. All are linked to the composer's work and are fervent admirers of his art, including the Swiss conductor Charles Dutoit, who called Penderecki “the greatest composer alive.”

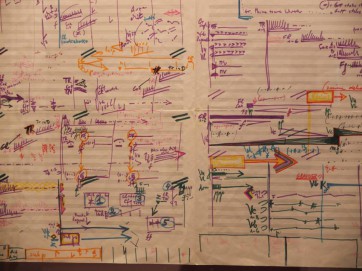

Penderecki also had an exceptional artistic journey, from the birth of his oeuvre after World War II. He ran away from “socialist realism” and started with the most radical experimentations, such as his Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima. However, he later came back to the tonal order, starting in the late 1970s with his imposing Symphony

No. 2. It may have been a progressive transition, but it was still regarded as treason by the keepers of the avant-garde flame. The festival was especially strong in its combining of works from all his creative periods, with all their strengths and weaknesses, both across its entire length and within individual concerts. In an awe-inspiring way, they revealed an exceptionally prolific musician (and, as such, radically anti-Boulez).

Works from the 1950s and 1960s, such as the Threnody or the beautiful De natura sonoris I, in which the orchestra instruments are used in an unexpected manner, have aged rather well. They still hold their orchestral power and the usual mastery of the technical possibilities of each instrument. Vocal music suits the composer particularly well; the presence of a text gives him the basis for a melodic line and a sense of color which are his trademarks. The brief prayer, Kaddish, composed in 2009 for the 65th anniversary of the destruction of the Jewish ghetto in Lodz, is strikingly dramatic, with its powerful texts, including one by Abraham Cytryn, a young writer from the ghetto, assassinated in 1944. The same is true of the Credo, an impressive work for soloists (soprano, mezzo-soprano, alto, tenor, bass), a children's choir, a mixed choir and a huge orchestra, which blends a defiant Neo- Romanticism with more complex effects from the use of massive numbers of voices and instruments. The inner power of this work, sometimes disproportionate, is still as staggering as its granitic tutti, strengthened by the use of an extended orchestra.

The fifteen concert pieces are central to the works of the musician. The horn concerto, “Witerreise”, created in 2008, is Penderecki's latest one to date. Composed after travels to China and South America, it is a perfumed journey through various instrumental moods, exploiting every technical possibility offered by the horn. The daunting Violin Concerto No. 1 (1967–1977) leaves us less convinced, with its darker shades and a post-Bergian opulence, characteristic of a transitional phase in the creator's stylistic evolution. In another register, the Concerto for three cellos (2001) lacks clearly identifiable forms and tends to meander in its developments.

Chamber music is another domain in which Penderecki excels. The brief Duet for violin and cello is made as subtly light as it is delightful by its dedicatees, Anne-Sophie Mutter (violin) and Roman Patkoló (cello). The slow Agnus Dei for string octet explores the limits of melody.

Chamber music is another domain in which Penderecki excels. The brief Duet for violin and cello is made as subtly light as it is delightful by its dedicatees, Anne-Sophie Mutter (violin) and Roman Patkoló (cello). The slow Agnus Dei for string octet explores the limits of melody.

As for interpretation, dizzying heights were reached by Polish choral and orchestral forces, gaining a place in hstory, for example, with the Sinfonia Varsovia or the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra of Katowice, led by conductors such as Leonard Slatkin, Gabriel Chmura, Charles Dutoit, Valery Gergiev, or the young prodigy Krzysztof Urbanski. Each one highlighted a different aspect of the musician's scores: delicate writing with Slatkin, sheer strength with Gergiev, mastery of structure with Chmura, sophisticated elegance wih Dutoit, dramatic literality with Urbanski. The soloists were no less excellent: the horn virtuoso Radovan Vlatkovi, the strong Polish violinist Konstanty Andrzej Kulka, and the prestigious cello trio of Arto Noras, Ivan Monighetti and Daniel Müller-Schott.

Crédits photographiques : Martin Hoffmeister/Pierre-Jean Tribot