Plus de détails

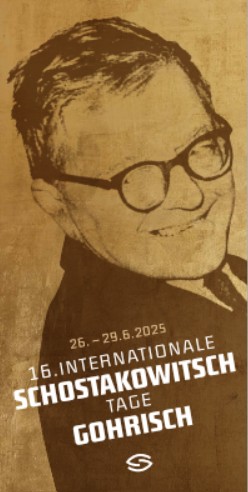

Paris. Salle Pleyel. 11-12-XI-2013. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) : Messe en do majeur op. 86 ; Symphonie n°4 op. 60 ; Dimitri Chostakovitch (1906-1975) : Symphonie n°6 op. 54 ; Symphonie n°8 « Stalingrad » op. 65. Luba Organasova, soprano ; Kelley O’Connor, mezzo-soprano ; Herbert Lippert, ténor ; Ruben Drole, basse. The Cleveland Orchestra chorus (chef de choeur : Robert Porco), The Cleveland Orchestra, direction : Franz Welser-Möst.

The Cleveland Orchestra has a prominent place, both among the greatest American orchestras and in music-lovers' hearts. It is indeed legitimately considered one of the famous “Big Five,” with some of the best conductors of the twentieth century, such as George Szell, Lorin Maazel, and Christoph van Dohnanyi, having conducted it.

The Cleveland Orchestra has a prominent place, both among the greatest American orchestras and in music-lovers' hearts. It is indeed legitimately considered one of the famous “Big Five,” with some of the best conductors of the twentieth century, such as George Szell, Lorin Maazel, and Christoph van Dohnanyi, having conducted it.

Its chief conductor has been Austrian conductor Franz Welser-Möst for a decade now. The orchestra is in great shape, and its coming for two concerts at the Salle Pleyel was eagerly awaited.

The night's program was quite atypical, since it did not include any short piece, nor any concerto. The concert was more of a comparison, or even a long-distance showdown, between two of the greatest symphonic composers in the history of music, namely Beethoven and Shostakovich. However, it was clear from the beginning that the German composer would fall by the wayside: his two programmed works were no match for the monumental pathos of Shostakovich's Eight Symphony, which was the peak of these two concerts.

The two works by Beethoven are seldom played, and perhaps understandably so: the Mass, for instance, which was poorly received at its premiere, appeared indeed quite inconsequential, despite a committed performance from both orchestra and soloists. Impossible though it might seem to catch Beethoven so flatfooted, this is indeed the case in this work, which aspires to the sublime without ever actually reaching it. It is filled with brilliant ideas, some clearly ahead of their time, but all no sooner glimpsed than forgotten. The Mass's inconsistency is undoubtedly the result of an inner struggle between Beethoven's respect for tradition (it is, after all, a mass) and his desire to renew the setting of the sacred text to music. As far as the interpretation is concerned, the choir clearly scored a home run. Its homogeneity and clear elocution especially were warmly received.

To round off the first concert, the orchestra performed Shostakovich's Sixth Symphony, also a lesser-known work, as innovative in form as it is quite unbalanced in structure, with an imposingly proportioned elegiac first movement followed by two much faster and shorter movements, in which the composer goes to great lengths to create a more relaxed atmosphere—to no avail. Nonetheless, this work displayed to good effect certain aspects of the orchestra's playing, such as the blending of timbres and the dialogues among various instruments, all executed flawlessly.

The next day two symphonies confronted each other. First came Beethoven's Fourth, which has the misfortune to be stuck between the Third and the Fifth. The Fourth is typical of Beethoven, but is less memorable than the other two, maybe because of its more pleasant character and lack of shadows. The superb Adagio was especially notable for its distillation of the orchestra's energy.

But then came the tidal wave of Shostakovich's Eight Symphony, which created, from the first notes of the opening Adagio, an atmosphere of grave solemnity, a mood extended through the two grating and cynical scherzi that follow and then in the noble passacaglia. Just as in the Sixth, the finale tries to resolve the symphony's numerous tensions, and, just as in the Sixth, it fails, leaving the listener a mere witness to the musicians' performance. The orchestra truly outdid itself in this work, and the soloists especially: piccolo, flute, clarinet, bassoon, and trumpet, among others. Many more deserve to be mentioned.

It was nonetheless disappointing when Welser-Möst chose to slow the tempo at the end of the second scherzo, no doubt to prepare for the tutti that serves to link the scherzo and the passacaglia—a debatable choice, since there is no such marking in the score, and it gives a dragging, frustrating feel to the music.

Nonetheless, after these two concerts, it seems perfectly clear that the band is not soon likely to lose its place among the ranks of the very best American orchestras—good news for music lovers.

Photo © Michael Pöhn

Plus de détails

Paris. Salle Pleyel. 11-12-XI-2013. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) : Messe en do majeur op. 86 ; Symphonie n°4 op. 60 ; Dimitri Chostakovitch (1906-1975) : Symphonie n°6 op. 54 ; Symphonie n°8 « Stalingrad » op. 65. Luba Organasova, soprano ; Kelley O’Connor, mezzo-soprano ; Herbert Lippert, ténor ; Ruben Drole, basse. The Cleveland Orchestra chorus (chef de choeur : Robert Porco), The Cleveland Orchestra, direction : Franz Welser-Möst.